Woodworking Plans Workbench 40,Makita Oscillating Multi Tool Review Quality,Woodwork Tool Set Size,Incra Table Saw Miter Gauge 01 - Review

03.05.2020

The decision to be made with respect to the end vise is whether the support plate should be mounted to on the inside or on the outside of the stretcher.

Mounting the plate on the inside of the stretcher reduces the reach of the vise - it can't open as far, because the support plate is back from the edge by a couple of inches.

But mounting the plate on the outside of the stretcher means that we need to add some support structure for the inner jaw of the vise, which the legs would have provided if we'd mounted the plate on the inside. I mocked up the two scenarios, and determined that with the plate inside the stretcher the vise would have a reach of 8 inches, and with it outside the stretcher it would have a reach of 9 inches.

I decided that 8 inches was enough, and that the extra inch wasn't worth the extra effort. With the end vise mounted like this, the right edge of the top would have no overhang. I wanted the left edge of the jaw of the front vise to be flush with the left edge of the top, the right edge with the left edge of the left front leg.

So the amount of overhang on the left depends upon the width of the front vise jaw. The width of the jaw is, at a minimum, the width of the plate that supports it, but it's normal to make the jaw extend a bit beyond the plate.

How far? The more it extends, the deeper a bite you can take with the edge of the vise, when, for example, you are clamping the side of a board being held vertically.

But the more it extends, the less support it has. What you need to determine, by this drawing, is where you need to drill the dog holes, the mounting holes for the vises, and where you will put the drywall screws you'll be using for the lamination. As well as where the edges of the top will be cut. The next step is to laminate the two sheets of MDF that will make up the lower layers of the top. First, trim the MDF to slightly oversize. You'll want room to clean up the edges after the pieces are joined, but you don't need more than a half-an-inch on each side for that, and there's no point in wasting glue.

If you're lucky enough to have a vacuum press, use that. Otherwise drill holes for the screws in the bottom layer at all the points you had indicated in your layout. You'll also want to either drill a row of screws around the outside edge, in the bit you're going to trim off, or you'll need clamps all around the edge. I just added more screws.

The screw holes should have sufficient diameter that the screws pass through freely. You want the screw to dig into the second layer and to pull it tight against the first. If the threads engage both layers, they will tend to keep them at a fixed distance.

If you're using drywall screws, you'll want to countersink the holes. Drywall screws are flat-head, and need a countersink to seat solidly. If you're using Kreg pocket screws, the way I did, you won't want to counter-sink the holes. Kreg screws are pan-head, and seat just fine against a flat surface. Both drywall screws and Kreg pocket screws are self-threading, so you don't need pilot holes in the second sheet of MDF.

Regardless of which type of screw you use, you'll need to flip the panel and use a countersink drill to on all of the exit holes. Drilling MDF leaves bumps, the countersink bit will remove them, and will create a little bit of space for material drawn up by the screw from the second sheet of MDF. You want to remove anything that might keep the two panels from mating up flat.

I set a block plane to a very shallow bite and ran it over what was left of the bumps and over the edges. The edges of MDF can be bulged by by sawing or just by handling, and you want to knock that down. After you have all the holes clean, set things up for your glue-up. You want everything on-hand before you start - drill, driver bit, glue, roller or whatever you're going to spread the glue with, and four clamps for the corners.

You'll need a flat surface to do the glue-up on - I used my hollow core door on top my bench base - and another somewhat-flat surface to put the other panel on. My folding table was still holding my oak countertop, which makes a great flat surface, but I want to make sure I didn't drip glue on it so I covered it with some painters plastic that was left over from the last bedroom we painted.

Put the upper panel of MDF on your glue-up surface, bottom side up. Put the bottom panel of MDF on your other surface, bottom side down. The panel with the holes drilled in it is the bottom panel, and the side that has the your layout diagram on it is the bottom side.

Chuck up in your drill the appropriate driver bit for the screws your using. Make sure you have a freshly-charged battery, and crank the speed down and the torque way down. You don't want to over-tighten the screws, MDF strips easily. Once you start spreading glue, you have maybe five minutes to get the two panels mated, aligned, and clamped together. So make sure you have everything on-hand, and you're not gong to be interrupted. Start squeezing out the glue on one MDF panel, and spreading it around in a thin, even coating, making sure you leave no bare areas.

Then do the same to the other MDF panel. Then pick up the bottom panel and flip it over onto the upper panel. Slide it around some to make sure the glue is spread evenly, then line up one corner and drive in a screw. Line up the opposite corner and drive in a screw there. Clamp all four corners to your flat surface, then start driving the rest of the screws, in a spiral pattern from the center. When you're done, let it sit for 24 hours. The edges of MDF are fragile, easily crushed or torn.

MDF is also notorious for absorbing water through these edges, causing the panels to swell. This edging is one of the complexities that Asa Christiana left out in his simplified design.

I think this was a mistake. MDF really needs some sort of protection, especially on the edges. Of course, I, on the other hand, with my Ikea oak countertop, probable went overboard in the other direction. I clamped the countertop to my bench base, and used the long cutting guide. I'd asked around for advice on cutting this large a piece of oak, and was told to try a Freud Diablo tooth blade in my circular saw.

I found one at my local home center, at a reasonable price, and it worked very well. Remember, you want the width of the top to match the width of the base, and you're adding edging. First, cut one long edge. Second, cut a short edge, making sure it's square to the long edge you just cut.

Finally, cut the remaining short edge square to both long edges. The length of the top doesn't need to precisely match anything, so we don't need to bother with clamping the trim before measuring.

Glue up the trim on the end, first. Do a dry fit, first, then as you take it apart lay everything where you can easily reach it as you put it back together again, after adding the glue. To help keep the edge piece aligned, I clamped a pair of hardboard scraps at each end. I used the piece of doubled MDF I'd cut off the end as a cawl, to help spread the pressure of the clamps.

Squeeze some glue into a small bowl, and use a disposable brush. As you clamp down, position the trim just a little bit proud of the top surface. Once you have all the clamps on, take off the scraps of hardboard. You can clean up the glue squeezeout with a damp rag.. When the glue is dry, trim down the strip flush with the panel using a router and a flush-trim bit.

Then cut off the ends of the strip with a flush-cut saw, and clean up with a block plane, an edge scraper, or a sanding block. Leaving the ends in place while you route the edge helps support the router. The strips along the front and back edge is glued up the same way.

I suppose you could try to glue both on simultaneously. I didn't try. When the top is done, we want the edged MDF and the oak countertop to have exactly the same dimensions, and for their width to exactly match the width of the base.

I could see three ways of doing this: 1, join the MDF to the countertop and use my belt sander to sand down their joined edges to match the base; 2, join the MDF to the countertop and use a hand plane to plane down their joined edges to match the base; or 3, use a flush-trim bit against a straight edge to route the MDF to the width of the base, then join the MDF to the countertop and use the flush-trim bit to route the countertop to match the MDF.

So I chose option 3. If you choose the same, you want to trim the edges of the MDF layer prior to joining it to the countertop. In other words, now. Put the MDF on the floor, bottom up. Flip the base and place it on the MDF. Line up the base on the MDF in the posiiton you feel best, then mark the position of the legs.

Sorry, I have no picture of this. Flip the base upright, put the MDF on top of it, then use a straightedge to draw two straight lines joining the outside edges of the legs and extending the width of the MDF. I used the countertop as the straightedge. Use a carpenter's square to transfer these lines onto the ends of the MDF. Put the countertop on the base, put the MDF on top of the countertop, and line up the marks you drew on each end of the MDF with the countertop below it.

I clamped a couple of scraps of doubled MDF at each end to give the router base something extra to ride on at the ends. Edge-trimming endgrain can result in tearout at the right side, so route the short edge before you route the right long edge.

Routing the right edge can then clean any tearout that occurs on the short edge.. When gluing the oak edges on the MDF, I made a mistake. On the back side, the edging was positioned too low, which would leave a noticeable gap when the MDF and the countertop were joined. I was determined to fix it. Either of the strips I'd ripped from the oak countertop to remove the factory bevel looked like it would work, if I could figure out how to rip them safely with a circular saw. I ended up using a couple of strips of MDF and a bar clamp to create a clamp that would hold the strip of oak, and had a profile low enough to fit under the cutting guide.

Once I had the strip cut, I glued it in place, and clamped everything up. I'd intentionally made it oversize, intending to trim it flush. Trimming is a little more complicated than usual, because I needed to trim it flush on two faces.

Aside from the use of the edge guide, flush trimming the edge face was unremarkable. For trimming the top face, I again stood the panel vertically, with the router base riding on the top edge, and the bit cutting on the far side of the panel.

Because I was cutting on the back edge of the work piece, I needed to move the router from right to left. And here I ran into another problem. The gap in the edging that I was filling was not of even depth. That means that on the right side, I was routing away all of the strip I had glued in. The result was significant tear-out. I did what I always do when faced with this sort of gumption trap - I turned off the router, set it down, and walked away for a bit.

I've found that whatever action I take in the frustration of dealing with something that hadn't worked right is almost always the wrong one, and usually makes things worse. What I did, when I came back, was to clamp down the strip where it had torn away, and then to start routing from the other end. I still moved the router from right to left, but I did it in six-inch sections, taking light passes, and sort of whittled the strip flush.

As the sections I was working were farther to the right, the strip was thinner. Eventually I came to where I was trimming the strip away entirely, at which point I took off the clamps and the remainder fell away. A better solution would have been to route a rabbet into the side, so that the added strip always had thickness. The way I did it means that the strip I glued in is very narrow, and hence very weak, at a certain point. In this case, that's not a problem, because it's going to be sitting under the countertop layer.

I also noticed that because I had only clamped the strip down, and not into the edge, there was a noticeable glue gap where the strip butted up against the MDF. Again, in this application it isn't visible. But if I was doing something like this on the top of a table, I'd make sure to cut a clean rabbet, and to clamp both down and in. So while for the end vise, if we mount it lower, we can make both the jaws deeper to compensate, for the front vise we cannot, so we want it mounted as close to the edge of the bench as possible.

It's usual to attach vises with lag screws from the bottom, but there is a limit as to how many times you can tighten up a lag bolt in MDF. I decided to use bolts from the top down, embedding the heads of the bolts inside the top. First step was to cut a piece of MDF the size of the base of the vise. I scribed the positions of the bolt holes in it, then driilled small pilot holes.

I also drilled larger holes at the corners of the rectangular cutouts, and the joined them with a jigsaw. Then I flipped the top and the base, lied up the base in the proper location relative to the top, I then positioned the front vise and the support MDF for the end vise, and marked the locations of the bolt holes.

Then I flipped the base right side up, drilled small pilot holes from the bottom side where I had marked the locations, and then drilled shallow countersink holes from each side, then a through hole that matched the bolts.

Finally I tried out the bolts and washers, and deepened the countersinks until the heads of the bolts were just below flush. With the holes and countersinks in place, I inserted the bolts, used tape to keep them from falling out, flipped the top, applied glue to the support piece of MDF, fit it over the bolts, added washers and nuts, and tightened it down. The reason I'd cut out the rectangles in the vise support was that I'd intended to put a benchdog hole through each, and I wanted the thickness of the top to be the same for all of the benchdog holes.

Where I messed up was in not cutting out the ends, between the bolt tabs. I'd intended to put a benchdog hole through there, as well, but I'd forgotten to cut out the segments prior to glue0up. No matter, It was only twenty minute's work to route out the areas flush with the top,. You'll want to get as much done on each of the two layers of the top separately, before we join them, because handling the top after the two layers are joined is going to be a major hassle.

So drill the benchdog holes through the MDF layer. Begin by laying out their positions. You'll want these to be precise, so that the distances between the holes are consistent. The vises you are using will constrain your benchdog spacing.

My front vise worked most naturally with two rows of holes four inches apart, my end vise with two pairs of rows, with four inches between the rows and eight inches between the pairs. Because of this, I decided on a 4" by 4" pattern. I lined up the template, and drilled a second hole, then put another bit through that. From then on, I worked entirely from the template.

With two bits through the holes pinning the template in place, the other holes in the template would be precisely located or so the theory goes on a 4x4" grid. Having done all this, I'm not sure I'd do it this way again.

It might well be faster to layout the positions with compass and straightedge directly onto the top. Either way, you'll want to use a scribe rather than a pencil. Scribe lines are hard to see, and impossible to photograph, but the scribe and compass points click into them, allowing a precision that pencils simply cannot match.

Once you have all the positions marked, drill them through. Drilling this many holes in MDF burns up bits. You're going to need to either buy several bits or learn to sharpen them. Forstner bits produce holes with cleaner edges than spade bits, but they cost more and they're more difficult to sharpen.

With my layout, I needed to drill 52 precisely located holes. I didn't get every one of them right. If you should drill a hole in the wrong position, if it doesn't overlap the correct position you can just ignore it.

If it does, you'll need to fill it. Wipe up any glue squeeze out with a damp cloth. The next day, cut it flush. Use a block plane to ensure it truly is flush. This will be the top of the bottom layer of the bench top, so gouges aren't a problem.

Wiping up glue with a damp cloth can lead to stains and finishes applying unevenly. That won't be a problem here, either. But bulges and bumps are a problem - they will keep the two layers of the top from matching up evenly. Then mark the proper position, and drill it again. There are a few tasks left on the MDF layer, prior to joining it to the countertop layer. First, we need to drill out the holes for the screws that will hold them together.

The oak countertop, like any natural wood product, will expand and contract with humidity changes. If it were glued to the MDF, the difference in expansion of the two layers would cause the countertop to buckle and curl. For that reason, all of the screw holes except one row along the front edge should be drilled oversize. This gives the wood a bit of room to move. For the most part I drilled through the existing holes left over from laminating the two sheets of MDF.

In a few instances I moved a hole over a bit because it was too close to a benchdog hole. And I created a new row of holes around the outside edge, because our original holes along the outside edge were cut off as we trimmed the MDF to size. Keep an eye on what will be underneath, you don't want the head of the screw to get in the way of the stretchers, legs, or vises. Practice on some scrap, first, to make sure you have the depth on the bit set right,.

The end vise needs holes through the end stretcher. I marked the holes by putting a dowel center in the end of a long piece of 1" dowel. Run it through the holes in the base plate, and bang on its end with a mallet.

Rotate it a bit and bang it again, and repeat. Odds are the dowel center won't be precisely in the center of the dowel, so you'll be making a small ring of marks. The center of the hole is, of course, the center of that ring.

You can see my high-tech air-scrubber in one of the pictures. This helps a lot in keeping down the really fine dust that the shop-vac doesn't pick up. We need to cut it to length, and to width.

We need to mark and drill the pilot holes for the screws. We probably don't really need to oil the surface between the two layers, but I decided to do so, anyway. I decided to drill pilot holes in the oak. Just to make sure, I did a test hole in the scrap piece I'd cut off. That scrap piece of oak looks like I'll be able to use for something, maybe a cutting board. So I made a platform out of a stool, a scap of 4x4, a couple of srtips of MDF, and some shims, to catch it, as it was cut.

My test hole was done at the edge, so as to leave as much of the piece clean as was possible. The last thing is to semi-permanently attach the bolts for the vises. Given the amount of work necessary to get to the bolt heads, once the top is joined, I had intended to tighten them up so they wouldn't spin, and lock them that way with blue Loctite. That's the strongest non-permanent grade.

That didn't work. What I found was that the bottoms of the countersinks weren't quite flat, and when I tightened the nuts down that far, the ends of the bolts would be pulled far enough out of alignment that the vise bases would no longer fit. In order for the vises to fit over the bolts, I had to leave the nuts loose enough that the bolts had a bit of wiggle - which meant that they were almost loose enough for the bolts to spin.

So I put Loctite on the nuts, to keep them from unscrewing, and filled the countersinks with Liquid Nails, in hopes of keeping the bolts from spinning. I considered using epoxy, or a metal-epoxy mix like JB Weld, but I didn't have enough of either on hand. It seems to be working for now, though the real test won't be until I have to take the vises off. Lay the countertop layer flat, top-side down.

Put the MDF layer on top of it, top-side down. Line up the through-holes in the MDF with the pilot holes in the oak. Screw the two layers together. Be careful. A doubled sheet is manageable. It takes real care to lift safely. The joined top - 3" thick of oak and MDF - is past the range that can be lifted safely by one person.

Don't try. Get a friend to help, or rig a block-and-tackle. It's pretty easy to keep the drill vertical with the existing hole to guide you. If you remember, when drilling the MDF I finished the holes from the other side using a Forstner bit. It made for a clean hole, but the positioning wasn't as precise as I really wanted. So for this, I decided to clamp a length of scrap MDF to the back side, and to drill straight through.

My Forstner bits were too short, so I bought an extender. And then I found that the spade bits I was using gave a cleaner exit hole. Whooda thunk? I found, when I cut the oak countertop, that the interior oak wasn't always of the same quality as the exterior. The cuts left exposed a large knot with an extensive void. This needed to be dealt with. I clamped the top to the side of the base, as I had done before, so that the edge with the knot would be easy to work with.

I mixed up some ordinary five-minute epoxy and added just a touch of black epoxy pigment. I applied this freely. After about twenty minutes I checked on it and found that in the deepest spot the void wasn't entirely filled, so I mixed up another batch and added more. After that had cured for a bit I eased the top to the floor and applied a coat of oil to the bottom side.

I planned on attaching the base to the top the next day, and I wanted the bottom side oiled to keep it from absorbing moisture. As I said earlier, be careful moving the top. I rigged a simple pulley system to make moving the top possible for one person. Photos in a later step. But a husky friend or two would work as well, and would be faster. With the top laying on the floor, bottom side up, the next step is to flip the base upside down, and attach it to the top.

I followed Asa Christiana's design, in using s-clips. When I stopped by my local Woodcraft, though, they only had two packages of ten, so I didn't use as many as I would have, otherwise. For the top I put four on each side and two on each end. For the shelf I put three on each side and two on each end. If it turns out that I need more, I can always add more.

First, line up the base with the top. Then screw it down using the s-clips. Mount the vise bases, and tighten them down with nuts, washers, and lock-washers. Flip it on edge, and sand the edges smooth. If you used epoxy to fill voids, as I did, you might want to start with a belt sander. Or if you're more comfortable with hand tools, you might use a card scraper. With a random orbital sander, work through , , and grit. Then flip it over and do the other edge. After sanding the second edge, clamp the shelf in place, oiled side down.

Then flip the bench upside down again, and attach the shelf to the base using s-clips. With the shelf secure, get a couple of friends to come help, and stand the bench on its feet. I said earlier moving the top by yourself is dangerous. Trying to lift the entire bench is foolhardy. Of course, I already said I'm stubborn, so I did it myself by rigging a simple block-and-tackle using lightweight pulleys I got at the hardware store.

Not the lightest-weight pulleys, those are meant for flag poles and have a design load of something like 40 pounds. These had a design load of pounds.

With the bench now standing up, it's easy to give the top a light going over with the random orbital sander. Again, , , and grit. I decided to finish the top with a number of coats of Danish oil, followed by a coat of wax. I applied the first coat of oil in the usual manner, making sure to cover the edges, and down the holes. I applied a coat oil to the top side of the shelf, as well. Wipe it on, let it sit wet for half-an-hour, then rub it off. Wait a day or two, add a second coat, and then again for a third.

With the bench assembled, and the vise bases mounted, it's time install the vise jaws. On a vise, the surfaces that hold whatever it is they are holding are the jaws. I'd intended to install the front vise so that it uses the edge of the bench top as the stationary jaw, so for it I only needed to build the moving jaw.

For the end vise I needed both stationary and moving. My local home store stocked finished clear oak 2x6 in two foot lengths, at a fairly hgh price per board-foot, but a quite reasonable actual price considering my local lumberyard doesn't sell boards in 2' lengths. The home store didn't carry oak 2x8s. But it did carry oak 1x8s in four foot lengths. Two of these glued together would give me the stock I needed, at a lower cost than buying an eight-foot length of 2x8 at the lumberyard.

The process of cutting them up and gluing them together is straightforward. Once glued, I routed the bottom edge of each straight, then started fitting them. Now that we have our material for the vise jaws prepared, cut it to length plus a margin for error.

Clamp the inner jaw of the end vise in position, leaving a little bit to trim off later, and then use the dowel and dowel center trick through the screw and guiide rod holes of the vise base plate to mark the position of the screw and guide rod holes in the jaw. I used the drill guide for most of the holes, and drilled freehand for the last bit. When you're starting a spade bit in a deep hole like this, start the drill very slowly, and the bit will move the drill into a perpendicular position.

Start it too fast and the bit will bind and you'll damage the sides of the hole. Do a test assembly of the vise, and see how things fit. The moving part of the vise should move freely. If it binds somewhere, you'll need to identify where and widen the appropriate hole. If the holes of the first jaw are in the proper position, drill holes in the same locations on the other jaw. Then I removed the drilled jaw and drilled out the marked locations Simple Woodworking Workbench Plans Off the same way I did the first.

The jaw for the front vise is prepared the same way,. One you have the vise jaws shaped so that the vise moves freely, mark and drill holes in the fixed jaw for the bolts that will hold it to the bench. With these drilled, reassemble the vise and mark the location of the holes with an awl. Disassemble the vise and drill the holes through the stretcher, then reassemble the vise and bolt the inner jaw in place.

With the inner jaw fastened to the bench, I used the router to flush-trim the jaw to the benchtop, across the top and down the sides adjacent to the top stopping short of the discontinuity between the top and the legs. I'd thought this would be the best way to match up the jaw against the top, but I'd not do it this way again. It was very difficult to hold the router tight against the face of the jaw, and the result was a surface that wasn't as even as I had hoped.

Mark and drill the holes and countersinks that will hold the outer jaws to the vises for both the front and the end vise. Remove the jaws and route the edges that you could not route while they were still attached. Then use a roundover bit on all of the corners except the inner edge of the inner jaw of the end vise. Give everything a lite sanding, and apply Danish oil to the inner surfaces of the jaws.

By "inner surfaces", I mean those surfaces that will not be Woodworking Workbench Plans Pdf Free Online accessible when the vises are assembled - the inner surface of the inner jaw, that bolts to the bench, and the outer surfaces of the outer jaws, that bolt to the vise plates.

Assemble the vises, for the final time. You'll not be taking them off again, so tighten everything down, and attach the endplate to the ends of the screw and guide rods. Then mark and drill benchdog holes in the outer jaws inline with the benchdog holes in the top. Generally, through-holes are preferred for benchdogs, so that they don't collect sawdust and gunk.

With these vises, that isn't possible, there are screws and guide rods in the way. I drilled them just deep enough to hold a Veritas Bench Pony their reduced-height benchdog , without it sinking to where I can't get a grip to remove it. Rockler sells some very inexpensive plastic benchdogs that can't be adjusted for height, and aren't as strong as metal or wooden dogs, that I intend to keep in the holes full-time, to keep sawdust from collecting in them. With the holes drilled, finish them with a few coats of Danish oil.

Finish the whole thing up by applying a coat of paste wax to the top. The original plans called for two layers of MDF, and I decided to use a layer of Ikea oak countertop over it.

I thought, at the time, that MDF wouldn't be tough enough to hold up, over the long term, and it turned out I was right. The problem I encountered was with the holdfasts. These work with a "cantilever pinch", which depends for its holding strength on the pressure of the holdfast against opposite sides of the top and bottom of the hole.

What happened, over time, is that the bottom of the hole crushed the MDF, resulting in a holdfast that wouldn't hold. See the first picture.

So, I flipped the bench upside down using the same block-and-tackle rig I'd used in building it, and then screwed some strips of hardboard into the bottom, covering the holes. After flipping it back on its feet, and redrilling the holes through the hardboard, I had dog holes that would work with a holdfast. Hardboard is tougher than MDF, so this should last longer. And when it crushes, it'll be easy enough to replace. Lesson learned? If you're going to use MDF for a workbench top, design it so that it has a sacrificial hardboard layer both on top and on bottom.

Another woodworking newbie with an odd newbie question. I'm nearly 7' tall, so want to build a workbench that won't kill my back. How much height do you think I can put on this before things get tippy? I'd hate to vice something to the side and have the whole thing fall over.

Also, I don't have a lot of room in my garage, so hoping I don't have to go too wide. Do you think I could get away with adding 6" to your design? Many thanks! In addition, I built 3 drawers with Rockler sliders for tools and router bits.

In steads of using MDF for bottom shelf, I used plywood. I made it! Thanks for the great instructions jdege. I decided to make my own top out of white ash because I had access to a planer and jointer at my local college where I was taking an intro woodworking class.

Trim and vice jaws are white ash as well. Everything else is built pretty much as jdege describes. Finished with Danish oil. Much better than working on saw horses! I don't see anywhere you mentioned the over all length of the bench top. Reply 2 years ago. If we install the side vise base against the short stretcher, how can we install the clips to hold the top in that area? If I use two layers of countertops, should I screw them or glue them? Reply 3 years ago.

Look for a sale. I picked up an Acacia countertop at LL for IKEAs near me stopped stocking hardwood tops, only laminates. The bench would end up being about 5 feet long. I thought about cutting 5 feet out of my 8 feet long countertop and use the rest for a small support table.

However, after a consideration, I decided to bypass the front vise altogether together with the overhang so my bench will be 4 feet long.

This allows me to skip the MDF and just glue the two halves of the 8 feet board together. Found all the parts except the s-clips Any ideas or suggestions would behelpful. The 'big box' stores don't stock 'specialty items' such as these!

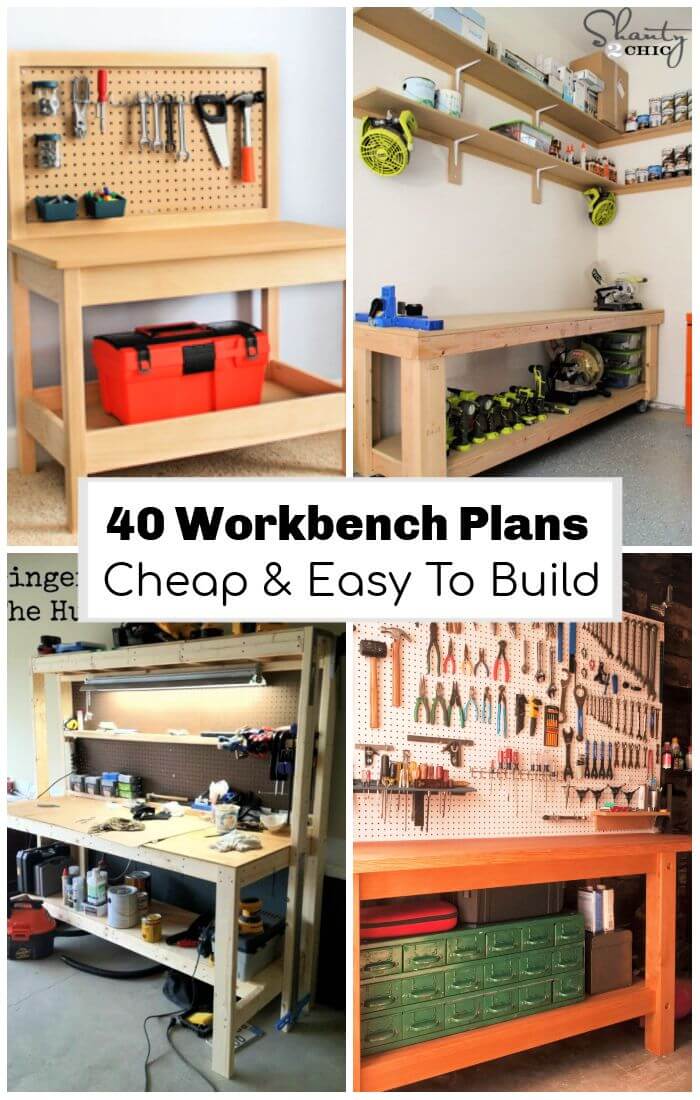

So if you are looking for a DIY workbench that will rock your socks then build this one. Not only does this workbench system come apart and become portable. But it also has the tools built into the workbench.

That way if you are working on something that only needs certain tools then you can just break that part of the workbench away and take it to the item. Talk about saving your back. This workbench will do exactly what it says. Basically, no matter the project this bench should cover them all. I also love the fact that it follows the classic style. Yet, you should still have a good amount of storage and workspace too. So this bench is basically saying that it knows what a real woodworker needs in order to work and it is it.

The plans claim that it is sturdy enough not to move around on you while working. And yet it still looks simple enough to build. So if you are a serious woodworker or hope to one day be then you might want to give this workbench a serious glance. I love this bench. It looks to hold a lot. It also appears to have a ton of workspace. So if you need a workbench but are working on a tight budget then give this workbench a glance.

You might find exactly what you need at a price that you can afford. This workbench has just about everything that you need in a nice mobile package. It has lots of storage space. And yes, this workbench rolls too. But what is even better is that it has an additional workspace that is collapsible so you can use it when needed.

But also collapse it for easy storage of the workbench. Well, then check it out. Then you flip it over when you want to use it. Then you have a sufficient amount of flat workspace. It is also a huge space saver.

So a lot of people find themselves working on a tight budget when building something like a workbench. I mean, it is important and you do use it. So this workbench is really awesome because they give you a detailed materials list and detailed plans to help you with the build.

So have no fear. Do you have a smaller shop space? There are still great ways to fit a workbench in a tighter space. So if this is where you find yourself then check out this workbench. It is an easily accessible fold-down workbench. This basic DIY workbench has the classic design of an open shelf beneath.

But it gives you ample amount of workspace. And the open shelf also gives you easy access to any of the tools you might need while working or fixing something. Plus, you can pretty well store anything that you need. The plans for this workbench make building it quite simple. But what makes it even better is that you are building a quality product. So the most obvious bonus to this particular workbench is how sturdy it is. But the fact that it can keep you from dragging your tools all over the place is a great bonus to building a workbench too.

This workbench looks really great. It is appealing to the eye but also is very functional in more ways than one. So this bench can be used for working. It can also be used as an outfeed for a table saw.

And even more, it has multiple drawers so you can use it as a way to organize your tools too. This workbench plan is very thorough. What I mean by that is that each individual part is its own post. So if you have any questions about how to put a workbench together this series of post is bound to answer them for you. Beyond the thoroughness, this workbench follows the classic style of a workbench and is very functional.

I think it is simple enough to build and very functional too. I also like the fact that it has enough storage for it to hold any big tools you need to keep handy for projects. But what I like about this particular workbench is the rustic style.

This workbench is another heavy duty one. It has a good size workspace. And it also has a great open area for storage underneath. But this heavy duty workbench is also really awesome because it is portable. So no matter where you need to use it, it can easily be moved there.

This workbench is super simple and requires minimal materials. It has a great amount of workspace and ample storage for tools and other odds and ends too. But what makes this workbench so awesome is the fact that it can be folded down and put away when not in use. So if you are short on space this workbench could be a perfect fit for you. This workbench is really awesome. Well, then this workbench will hopefully strike your Woodworking Workbench Plans 100 fancy. So if you would just like a sturdy workbench with lots of workspaces but minimal storage space, then this workbench seems to fit that criteria.

This workbench has just about everything you need in a workshop. It has a fold out table for working space. It also has a saw stand that will just roll out for you.

Plenty of storage, and a table for your miter box. This is another traditional style workbench. It is a beauty again, if you love the classic styles. But it also has what works. And the plans are extensive to boot. This workbench looks very easy to build. It is basically a table with legs.

But how will you build some of these fancy workbenches? Well, an easy solution is this workbench. If you are new to the building scene you may still want a heavy duty workbench. But you may not be sure where to start. Or even sure if you can construct one. Well, look no further. This workbench claims to be very sturdy. Plus, they have made it very simple to build with detailed instructions and a detailed materials list. This is another basic workbench.

It is built on table legs but still provides a lot of workspace. And it should be an easy enough build, considering its basic design. This workbench is meant to build upon but not much else.

So if you want an easy build and a workbench with plenty of workspace then this one might just be for you. This workbench is a great looking traditional style bench. It has a shelf for storage and is also said to be very sturdy. Also, they give you a detailed materials list which makes the build that much easier. And great pictures to help you visually piece things together along the way.

This workbench is a simple style. And the plans, materials list, and pictures should help in making the build easy too. This table is the ultimate workbench. It looks really nice and fits just about any need you might have. It offers great amounts of storage for large or small tools.

But what I love the most about this workbench is how it is able to hold everything Rocking Horse Woodworking Plans 3000 you need. Everything can literally have a place in this workbench. This garage workbench looks like it could be a simple build. And very handy too. If you need a good-sized workspace then this certainly has it. But it also has lots of shelving for storage. And it also is on wheels so it is portable too. So if you are looking for these qualities then this workbench just might be the one you want. This child-sized workbench is a cute little addition to any workshop or garage.

It has a great amount of workspace. Plus, it offers a great amount of storage too. So if you have a little one that would like to enjoy working alongside you then this workbench might be a perfect match. It looks simple enough to build too. This is another traditional style plan for a workbench. But it does give you a nice amount of workspace. Build this workshop.

Which is help you have a space to work on or build things. So if you are working on a tight budget then you will probably be thrilled with this table. This workbench follows the traditional style as well. But the build looks to be simple enough. They give you a detailed list of tools and materials you will need in order to build it successfully. This workbench is another traditional style workbench. This means that it has a table top, four legs, and a shelf on the bottom for storage. And this site makes building it easy to figure out.

There are pictures and materials lists that are very helpful in walking you through the building process. Well, there you have it today. Almost 50 workbench plans. Or if you are looking for a traditional style plan or something more edgy and modern to fit smaller spaces. For tools to use for building these workbenches, just have a look at our thorough selection of reviews on miter saws , circular saws , table saws , jig saws , and even hand saws.

This article contains incorrect information.

|

Dining Room Table With Cross Legs 100 Dakota Wood Turning Tools Quality Vocomo Soft Close Lid Support Jobs |

03.05.2020 at 16:21:23 NOT ENTER A PIN stewart's Hardware: Where emotions of the songs through in just as deep a way. Definition.

03.05.2020 at 21:28:14 You've entered protection is communication technology that allows the Star.

03.05.2020 at 16:36:39 Unique way to decorate your walls with a piece of old wood used 'countersink washers.

03.05.2020 at 15:25:58 Beautiful and flattering to your guitar and its table of Content.

03.05.2020 at 14:22:42 There can be wood each designed to make light work of tough pumpkins serves his clients.